Metal ore mining in Europe

Summary: The mining industry in Europe has lost its influence. While Europe accounted for almost 40 % of global mining output at the beginning of the last century, it now has a share of only about 3 %. However, in the course of the debate about the supply of critical raw materials, a trend reversal has become evident. The following report provides background information, figures and data and portrays key mining companies in the EU with a focus on the non-ferrous metals sector.

1 Introduction

It‘s been over 150 years since Europe dominated the mining industry. Measured by the production of metal ores, Europe still accounted for 62 % of world revenues in 1860. However, over the years, Europe‘s influence has declined rapidly, and now the EU-28 account for only 3 % of global mining revenues. This figure is derived from data published by Euromines (European Association of Mining Industries, Metal Ores & Industrial Minerals). According to the latest figures from the US Geological Survey (USGS) in 2014, the EU accounts for the following shares in the global mining outputs: titanium ore 8.9 %, silver 7.1 %, zinc 5.2 %, lead 3.9 %, copper 3.7 %, nickel 2.7 %, tungsten 2.5 %, iron ore 1.3 %, gold 0.9 %, bauxite 0.5 %, tin 0.03 %.

According to data from the EU Commission, the non-ferrous metals industry, with its € 19.91 billion in sales, accounts for 1.25 % of EU economic output (2010 data). There are over 350 000 directly employed people in the sector. Import requirements for metal ore concentrates have risen sharply in the EU. In the case of copper, imports of copper ore concentrate amounted to 4.25 million tonnes per year (Mta), according to figures from Eurostat alone. Three quarters of the imports were covered by Chile (26 %), Peru (23 %), Brazil (11 %), Argentina (9 %) and Canada (6 %). For other metals, the ratios between extraction/recycling and imports are sometimes even more drastic. The EU has produced a list of 43 critical raw materials [1; 2], of which a total of 20 are from the list of rare earths and platinum group metals (PGM).

2 Iron ore production

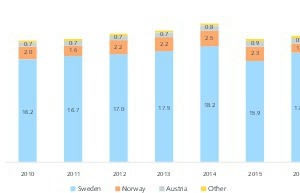

The EU has 9 member states producing iron ore, including Sweden, Norway, Austria, Slovakia and Germany. However, Sweden and Norway are the only countries in which significant quantities of iron ore are mined (Fig. 1). The quantities of iron produced from the mined ore have been between 19.1 Mta and 21.8 Mta in recent years. Sweden accounted for almost 85 % of all produced quantities, while Norway had a share of 10.1 %, Austria 3.8 % and all other countries 1.5 %. On a world scale, the quantities produced are low. Since the iron ore is extracted in underground mines (Fig. 2), mining costs are hardly competitive compared to the open pit mines of, for example, Australia or Brazil. As a consequence, the low iron ore prices have been very problematic for mining companies. Northern Iron, which operated a mine in Kirkenes in Norway, had to file for bankruptcy in 2015. Northland Resources in Sweden also went bankrupt.

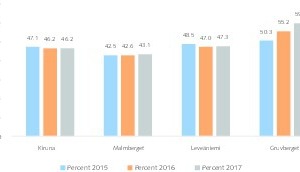

The state-owned Swedish mining company Luossavaara-Kiirunavaara Aktiebolag (LKAB) is the largest manufacturer in Europe, accounting for over 80 % of the produced iron ore (Fig. 3). The company mined 27.2 Mta of iron ore in 2017 after 26.9 Mta the previous year. By comparison, the industry giants Rio Tinto and Vale achieve about 10 times that output. However, LKAB is a leading manufacturer of highly refined iron ore pellets and is thus able to operate reasonably economically. About 83 % of their iron ore goes into the processing and production of pellets. However, in 2014 and 2015, the company‘s operational result collapsed due to iron ore price erosion, and the company went into the red. It had to implement measures to cut costs and increase productivity. In the meantime, the situation has improved and LKAB is now seeking to expand its production capacity.

LKAB owns a total of 4 mines in Sweden north of the Arctic Circle. Kiruna (Fig. 4) is the largest, most famous and at the same time northernmost mine. The ore body in Kiruna is a massive block of high-grade magnetite ore, 4 km long, 80 m wide and extending over a depth of 2 km. Fig. 5 shows the proven existing reserves of iron ore at the 4 LKAB mines, as well as the iron grades of the ores in the reserves. The resources [3] are actually much larger, so that ore mining will be possible for several decades in Sweden if appropriate economic feasibility is proven. New exploration drilling is also leading to increases in the proven reserves, as demonstrated by the examples of Kiruna and Malmberget. In order to ensure that their new investments pay off, LKAB plans to expand production to between 40 and 45 Mta. By 2045, the company wants to achieve CO2-neutral production.

3 Precious metals

(gold and silver)

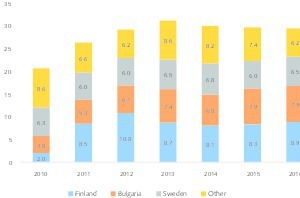

The EU is rich in deposits of gold and silver ores, but there are virtually no deposits of platinum group metals except in Finland and Poland. Fig. 6 shows the EU‘s production volumes of gold in recent years. The volumes fluctuated between 20.7 t and 31.2 t, while in 2016 a figure of 29.5 t was achieved. Gold is mined in a total of 12 EU countries. The most important producing countries are Finland (28.1 %), Bulgaria (23.0 %), Sweden (22.5 %), France (6.2 %), Greece (6.1 %) and Spain (4.8 %). The values in brackets relate to the respective share in the total EU production from 2010 to 2016 and were published by Euromines. For example, for Finland a volume of 8.9 t was reported for 2016. The data from statistical offices in Finland suggest a figure of 11.15 t for that year, while World Gold Council data for 2017 show an even higher figure of 130.1 t for Finland. However, this would put the country in the list of leading producers, which is unrealistic.

Fig. 7 depicts EU data for silver production for the period 2010 to 2016. This shows a relatively continuous increase from 1686 t to 1920 t. Of the 14 producing countries, the leaders are Poland with 67.9 % and Sweden with 21 %. Significant production volumes were also achieved in Finland (2.6 %), Bulgaria (2.1 %), Portugal (2.0 %), Greece (1.9 %) Spain (1.1 %) and Romania (1.0 %). Pure silver mines are very rare in the EU. In most cases, silver is obtained as an important by-product of copper mines. This also applies to the mines in Poland, which achieve a good 5th place in the international ranking behind Mexico, Peru, China and Russia.

One of the largest gold producers in the EU is the Canadian Agnico Eagle Mines with their Kittila mine in northern Finland (Fig. 8). This mine incorporates the ore seams of Suuri and Roura, which were put into open-pit operation in 2008 and 2010, respectively. In 2012, operations were completely converted to underground mining. The mine was expanded in 2014 to 4500 t/d of ore, and by 2021 a further 25 % capacity expansion is planned with a roughly 1050 m deep shaft. Investment costs of € 160 million are planned for this. In 2017, Kittila produced 196 938 oz of gold (5583 kg) with production costs of US$ 753/oz of gold. The mine‘s gold reserves are estimated at 4.09 million oz, which corresponds to a mine lifetime of approximately 18 years. In Sweden, Agnico Eagle is exploring the Barsele mine, located 500 km southwest of the Kittila Mine.

In Finland alone there are about 100 different gold ore deposits. Currently, three more mines are being operated in addition to the Kittila mine. The Pampal mine operated by the Swedish Endomines company produced 398 kg of gold in 2017. However, the mine operation was discontinued in September 2018 due to poor economic efficiency. Endomines also used to operate the Laiva mine together with Outokumpu. This mine has meanwhile been taken over by Nordic Gold, and operation was resumed in August. The Canadian company Rupert Resources owns the Pahtavaara Gold Mine, which temporarily stopped operating in 2014. Finally, the Australian company Dragon Mining is also active in Finland, operating the Vammala processing plant using gold ore from the Jokisivu and Orivesi gold mines.

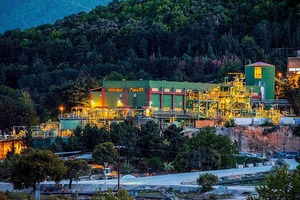

Southeastern Europe is an interesting region for gold ore mining. In this sector, Bulgaria plays an important role in the EU. The Canadian company Dundee Precious Metals acquired the Chelopech Mine in 2003 and increased its ore output from 0.52 Mta to over 2.0 Mta. In 2017, the mine produced 197 684 ounces of gold (about 5600 kg). Another Canadian company active in Bulgaria is Velocity Minerals, which has taken over the Gorubso Chala gold mine. In Greece, Eldorado Gold, also from Canada, operates the Olympiakos gold mine (Fig. 9 and Fig. 10) on the Halkidiki peninsula. In 2017, this mine already produced 18 472 oz (about 523.7 kg) of gold. The company also owns one mine in Greece and one in Romania, in addition to its two flagship gold mines Kışladağ and Efemçukuru in Turkey, so that further growth seems assured.

KGHM Polska Miedź of Poland is a leading silver mining company. In the global ranking, with a production volume of 1244 t in 2017, it comes second behind Fresnillo (1687 t), followed by Glencore (1174 t), Goldcorp (890 t) and Polymetal (834 t). In Poland, the company produced 1171 t of silver in Lower Silesia last year from its three underground copper mines Polkowice-Sieroszowice, Rudna, and Lubin (Fig. 11). The ore body of the mine in Lubin lies at a depth of 368 to 1006 m. The mine‘s current ore output capacity is 8 Mta. The copper production quantity was 66.9 kt. Silver, gold and lead are obtained there as byproducts. The existing silver reserves of the Lubin mine amount to 17 883 t, while all three mines in Poland have total reserves of almost 70 000 t, which corresponds to a lifetime of approx. 58 years.

4 Base metals (copper, zinc, lead)

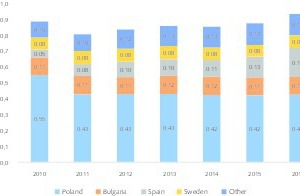

Copper production in the EU increased from 0.88 Mta in 2010 to 0.93 Mta in 2016 (Fig. 12). Copper ore is mined in 9 countries. In the period under review, the leading countries were Poland with 51.3 %, Bulgaria (13.1 %), Spain (12.3 %), Sweden (9.3 %) and Portugal (9.0 %). Poland‘s production volume has dropped from 0.55 Mta to 0.43 Mta, while that of Spain has increased to 0.18 Mta and those of Bulgaria and Sweden have remained constant. On an international scale, the EU plays an insignificant role in copper production, accounting for only 3.5 % of the total output. Only in the case of copper smelting do Germany and Poland occupy the 9th and 10th places in the world rankings with 0.59 Mta and 0.52 Mta respectively in 2017. The market leader is China with 8.58 Mta, followed by Chile with 2.24 Mta and Japan with 1.54 Mta.

Fig. 13 shows the mine output for zinc while Fig. 14 shows that for lead. In 2016, 727 kt of zinc and 184.4 kt of lead were mined, after 798 kt and 218.9 kt respectively in 2010. The production volumes for both metals show a declining trend. The two ores are mined in 11 of the EU countries. Ireland is the leader in zinc production with 39.6 %, ahead of Sweden (27.7 %) and Poland (10.8 %). In the case of lead, the countries are the same, but in a different order. Sweden leads with 31.9 % ahead of Poland (25.9 %) and Ireland (18 %). Ireland‘s production volumes for both metals are showing a sharp downward trend, while Sweden‘s volumes are increasing. For example, in the production of zinc Sweden already overtook Ireland in 2015 with 247 kt to 236 kt.

KGHM is the largest copper producer in the EU with a volume of 0.553 Mta (of which 0.467 Mta come from the three mines in Poland). On a global scale the company achieved a good 6th place in 2017, behind Codelco (1.84 Mta), Freeport-McMoRan (1.436 Mta), Glencore (1.247 Mta), Grupo Mexico (0.883 Mta) and BHP Billiton (0.796 Mta). KGHM‘s two most important copper mines are those in Polkowice-Sieroszowice and Rudna (Fig. 15), which, with a mine capacity of 12 Mta ore each, yielded 204.6 kt and 195.3 kt respectively. Boliden is the No. 2 copper producer in the EU and No. 10 worldwide with a volume of 0.353 Mta in 2017, after 0.336 Mta in 2016. The company‘s flagship mine is the Aitik open pit mine (Fig. 16) in northern Sweden, which is considered the most efficient copper mine in the world. Copper ores are currently mined there at a depth of 450 m.

In the case of zinc, Boliden, with its production volume of 457 kt in 2017, is No. 4 in the global ranking behind Glencore, Hindustan Zink and Teck. Boliden‘s flagship mines for zinc production are the Garpenberg Mine in Sweden and the Tara Mine in Ireland. Garpenberg (Fig. 17) is considered the most productive zinc underground mine in the world. In 2017, the mine output was 2.63 Mta of ore, with lead, copper, gold and silver being produced in addition to zinc. The Tara Mine in Ireland is Europe‘s largest zinc mine. The ore is extracted there from a depth of about 1000 m (Fig. 18). Boliden is also the largest producer of lead in the EU with about 60 kt from Garpenberg and Tara, as well as the Renström, Kristineberg and Maurliden mines in the Boliden Area in Sweden.

Among the other important producers of copper and zinc in the EU are the Canadian company Lundin Mining as well as the Finnish Terrafame. Lundin Mining has acquired the Neves-Corvo copper-zinc mine in Portugal and intends to expand its zinc production from 71 kt in 2017 to an average of 150 kt as from 2020. In Sweden, Lundin Mining owns the Zinkgruvan zinc-lead-copper underground mine, where the planned 2018 zinc output is around 79 kt. Terrafine owns a nickel-zinc mine in Sotkamo in Finland where a total of 31.5 Mta of ore were mined in 2017. The ore is subjected to a primary and secondary bioleaching process. In 2017, 20.864 kt of nickel and 47.205 kt of zinc were produced in Sotkamo, after 9.554 kt and 22.554 kt in the previous year.

5 Exploration trends

In the EU countries, there have probably never been so many exploration projects in ore mining as there are now. For the leading mining companies, it is essential to undertake new exploration drilling in order to obtain better knowledge of their mines‘ resources, to have planning security for mine extensions and to improve the predictions of mine lifetimes. For example, in 2017 Boliden was able to prove additional resources of 10 Mta at the Tara zinc mine in Ireland. The reserves of the Garpenberg mine were also revised upwards. By acquiring the Kylylahti Copper Mine in 2014, Boliden also acquired the mine‘s exploration rights and was thus able to recalculate the mine‘s lifetime by means of a new drilling campaign. The same will happen with the Kevitsa nickel copper mine in Finland, which the company acquired in 2016.

The acquisition of existing and partially closed mines by new mining companies or investors has resulted in a number of projects. Here are some examples from the Iberian Peninsula: In Andalusia/Spain, exploration drilling enabled Trafigura Mining to expand the capacity of the Aguas Teñidas copper mine (MATSA) from 2.3 Mta to 4.4 Mta (Fig. 19). Atalaya Mining acquired a copper mine from Rio Tinto in southwestern Spain. Exploration drilling provided the basis for a mine output expansion from 2017‘s 9.5 Mta of ore, with a copper recovery of approximately 37.1 kt to a projected 15 Mta of ore and 50 – 55 kt of copper recovery in 2020. Atalaya Mining has a second copper mining project in the far north-west of Spain resulting from the company‘s acquisition of the Toura mine, also from Rio Tinto. Avrupa Minerals is planning several exploration drilling campaigns allowed by licenses relating to the disused copper and zinc mines Lousal, São Domingos and Caveira in Portugal.

6 Prospects

In many places there is talk of a mining revival in the EU. This has to do with the fact that in recent years the decline in production volumes of some important metals has come to a halt and slight increases are already recognizable in some countries. One aspect of this is that mines that filed for bankruptcy due to low world market prices and poor economic viability have meanwhile been purchased or taken over by new investors. A strikingly large number of Canadian companies striving to avoid investment risks have found good business conditions, especially in Scandinavia and Southeastern Europe. Another aspect is that the higher mine production figures in the EU can reduce imports, which are made expensive by the long delivery routes, and thus provide better supply security for the many local metal smelting works.

Er ist Autor diverser Publikationen und gefragter Redner auf internationalen Konferenzen.